What do we make of the story of Abraham and Isaac? Of Hagar? Of Sodom and Gomorrah?

Faith Matters resources to accompany your Come Follow Me study: Feb 23 - March 1

The Lord fulfills His promises in His own time.

We, like Abraham, might be holding out hope for deliverance, and, as the knife draws ever closer, wondering if we were mistaken—if deliverance might not come. I believe the reader is meant to feel the agony of this experience, which throws into even sharper relief God’s deliverance at the very last moment.

This is not an experience I ever want to feel comfortable with or hear a satisfying answer for. It should feel extreme. It should feel horrifying. I think its literary power depends on that.

At the same time, allowing the story to put Abraham’s children in danger is a powerful literary device that drives home the ultimate point that nothing can prevent God from keeping God’s promises—not even God. God is faithful, even when faithfulness seems impossible, and even when it seems like God is the very Being who has betrayed or abandoned us. To an ancient audience acquainted with death, displaced from their homes, feeling like there was no possible way God’s promises to them could be fulfilled, wondering if God had in fact forgotten or betrayed or abandoned them, I can imagine this being an incredibly powerful reminder.

And so I don’t read this as much as a story about Abraham’s faithfulness to God as I do a story about God’s faithfulness to Abraham, and so to all of us. Even when it appears that God (or that following God) is the very source of our troubles and distress, God is faithful and God will deliver.

—Cecelia Proffit, “The God Who Sees”

The times when God most wishes he spoke English are the times when he wouldn’t know what to say. The times when you’re praying so hard for something but it’s just not meant to be. The times when a wish you held dear is shriveling and he can see it’s going to die and he can see it’s going to take a piece of you with it. The times when someone hurts you, terribly, and you go over it all in your mind again and again wondering what you could have done differently—and that’s exactly the wrong question but it’s also the only question that gives you any sense of control. In many of these moments, God is as silent as the ashes left when the fire dies down. If he could, he would be silent in English, in your language, so that you could know that it’s not an absent silence but an active silence. A stilling of the soul of the universe in solidarity with your distress. A witness. God is never quite so focused on you as when he doesn’t speak.

—James Goldberg, “A Secret”

The Lord commands me to flee wickedness and not look back.

I no longer flee darkness. I now seek light.

—Ethan Unklesbay, “Haibun for Lehi”

From a transformative perspective, worldliness is any attempt to find security through finite means—safety, pleasure, the esteem of others, and the insatiable need to control our circumstances. The gospel invites us to leave this worldliness behind and find security in the only Reality that is worthy of our hearts. We are not sanctified by perfecting the false self but by waking up to an entirely new dimension of self, whose center of gravity is Christ.

—Thomas McConkie, At-One-Ment (read an excerpt here)

The scriptures are full of stories of people being commanded to flee wickedness. The stories of the Nephites and Jaredites in the Book of Mormon gives us unique insight on what it means to “not look back”:

God's promise in the land is fulfilled only in a community of solidarity, love, and humility. The promised land is not a reward, a deserved birthright, or a promise of superiority. Rather, this disquieting truth emerges: The promise of God is found in how we live, not in where we live. Indeed, the promise of God in the land is not a guarantee of unchallenged continuity, dominion, and prosperity. The cycle of prosperity and destruction in the Book of Mormon is a cautionary tale, calling us to confront ourselves.

—Jenny Richards, “The Promised Land: A Cautionary Tale”

What did Lot’s wife do wrong?

“…But the men had not come for pleasantries. They carried a message. A big, terrible, tragic, sad, horrible, unbelievable message. Sodom, the bustling city they lived in, was about to be destroyed. “Your walls will not protect you from this,” they explained. “Leave now and don’t look back.”

So Lot and his wife grabbed their two youngest daughters and a backpack with toothbrushes, water, and snacks, and headed out the door. But before they could go, they had to warn their oldest daughters, their son-in-laws, and their grandkids.

But the son-in-laws thought it was a joke, and the eldest daughters didn’t want to wake the children, and they didn’t even believe in angels anyway, and the whole story all felt a little ridiculous. It was probably just another trick to get them to come back inside the walls. But they were not going to be duped. They were not going to be scared. They were not going to leave. Yet Lot’s wife persisted. “If you’re not going to come with us now, promise us you’ll run at the first sign of danger. Don’t wait a second longer. Promise me, please. Promise me.”

And off Lot and his wife and their two youngest daughters went. They ran out beyond the city wall and down the road. They ran through the night and into the morning. As the sun was rising, Lot’s wife trailed behind the other three. Her run became a jog and then a walk. She looked ahead at her youngest daughters, who were moving swiftly away from danger. And then all at once, she looked back. She had to see if the rest of their family was following or if an army was coming or what terrible destruction might be approaching.

Maybe there was still something she could do for her eldest daughters. Maybe they’d see the danger in time. Maybe they’d still come running. Maybe she could help carry the children. But her youngest daughters also needed help. They weren’t safe yet. Plus, they were the ones who listened. But they were not in as much danger. And she didn’t know if she should help the people who needed it most or the people she was most able to help. And so she didn’t know if she should move forward or go back. She was stuck in paralysis.

Paralysis, a definition:

So often in life, we are stuck. Not between a rock and a hard place or in the mud or from a headlock. More often, we are stuck between two good choices. Do you want licorice or gummy bears? This toy or that one? To clean or to play? These are all good things, and sometimes you will get stuck picking between them. You won’t be able to decide whether to go north or south, left or right, up or down. You will want to pick the best option, but you won’t know how. And so you will be stuck trying to figure out what to do. This is paralysis.

Lot’s wife was in paralysis. She couldn’t decide to go forward or backwards. She stood frozen like a pillar halfway between them, her eyes looking back but her feet facing forward, not moving an inch either direction.”

Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice Isaac is a similitude of God and His Son.

I can trust God to keep His promises.

Here, and in later chapters, we see a God who is relational—a God who can be talked to, questioned, negotiated with, and argued with. We see a God who wants to be in committed relationship with humanity, a God willingly and actively bound to another person in a covenant relationship. Notable to me is that in this relationship, God goes first; the only thing required of Abram at this point is willingness and trust. We might see here a reflection of a principle taught in the First Epistle of John—“We love [God] because [God] first loved us.”

—Cecelia Proffit, “The God Who Sees”

Abraham obeyed the Lord.

I don’t think I believe in “Abrahamic tests.” An “Abrahamic test” is God asking us to do something that is in clear violation of moral law and our conscience, in order to demonstrate that our obedience is to God, and not to any deeply held sense of right and wrong.

God is saying: “You must trust and obey me, even if I ask you to do something that seems unambiguously and monstrously evil, like slitting your child’s throat.”

I need scarcely begin enumerating the evils committed in history by people who thought they were acting according to God’s command, or at least with God’s approval. Examples are numerous and usually catastrophic. They give us good reason, rooted in human experience, to distrust any notion that God might in certain instances override “moral law” just to prove he can do it.

But there’s an even better reason to question the “Abrahamic test” idea. I actually think we misread and misunderstand the story of Abraham and Isaac.

Travel back to Abraham’s time. Abraham grew up in a world in which deity was to be placated. Humans generally believed their survival and prosperity depended on staying on their god’s good side. Gods controlled things over which humans had no control—rains, floods, drought, pestilence, invasions, etc. So people often offered up a portion of their harvests or flocks, partly in gratitude but mostly to keep the gods happy and on their side.

But the gods could be fickle and unpredictable. Sometimes the sacrifices didn’t seem to be enough. How would you ever know for sure if you had offered enough to make your god happy? Better to err on the generous side, so just to make sure the gods were sufficiently appeased, many ancient cultures would offer the most valuable thing they had: human life. Men, women and children were put on the altar to appease a jealous, fickle, but powerful god.

We are given to understand that Abraham himself was nearly offered up on the sacrificial altar before his escape from Ur. And so it would have been a great disappointment, but perhaps no great surprise, when God told Abraham to do the unthinkable: kill his only son. After all, Abraham probably thought, that’s what gods sometimes require. Abraham’s god was acting just like all other gods in his world.

And so, the way we usually tell the story, Abraham proved his faith and love for God by his willingness to take a blade and slit the throat of his obedient son Isaac.

Except that he didn’t; and this was the moment history began to change.

In that very dramatic moment in which Abraham draws his knife, God sends an angel to stop him, and by stopping him, God will teach Abraham and Isaac (and the world) the most revolutionary truth of all.

“Abraham, stop! No, I am NOT the kind of God who would ask a man to murder his son.”

“I am NOT the kind of god your fathers worshipped. I am NOT capricious and vengeful and egotistical and bloodthirsty.

“I am NOT the kind of God who would ask you to do monstrous and morally repugnant things. On the contrary, I want you to learn to become moral and good.”

“I am your Father. I am merciful. I can be trusted. I love you and I love your son Isaac. I want to enter into a covenantal relationship with you.

“I’m NOT waiting on your sacrificial gifts before I will bless you. I have gifts for you now if you love me.”

And so God’s first gift to Abraham was the ram in the thicket. But that was only the beginning. God is going to show Abraham what His love is really about, blessing him so richly that, through Abraham, all of humanity would eventually be blessed.

—Bill Turnbull, “Is Abraham’s story really our story?”

Explore the covenants of obedience, sacrifice, and consecration in this episode of Sanctuary:

Big Questions

One of the most difficult aspects for me to reckon with when reading the Old Testament is that, while these are literary stories communicating a larger message about God, many also portray human experiences in which God appears to command or condone things I believe are deeply immoral. How can we simultaneously find devotional value and literary power in a story while strongly condemning immorality and naming what’s wrong as unequivocally wrong? Should we even try?

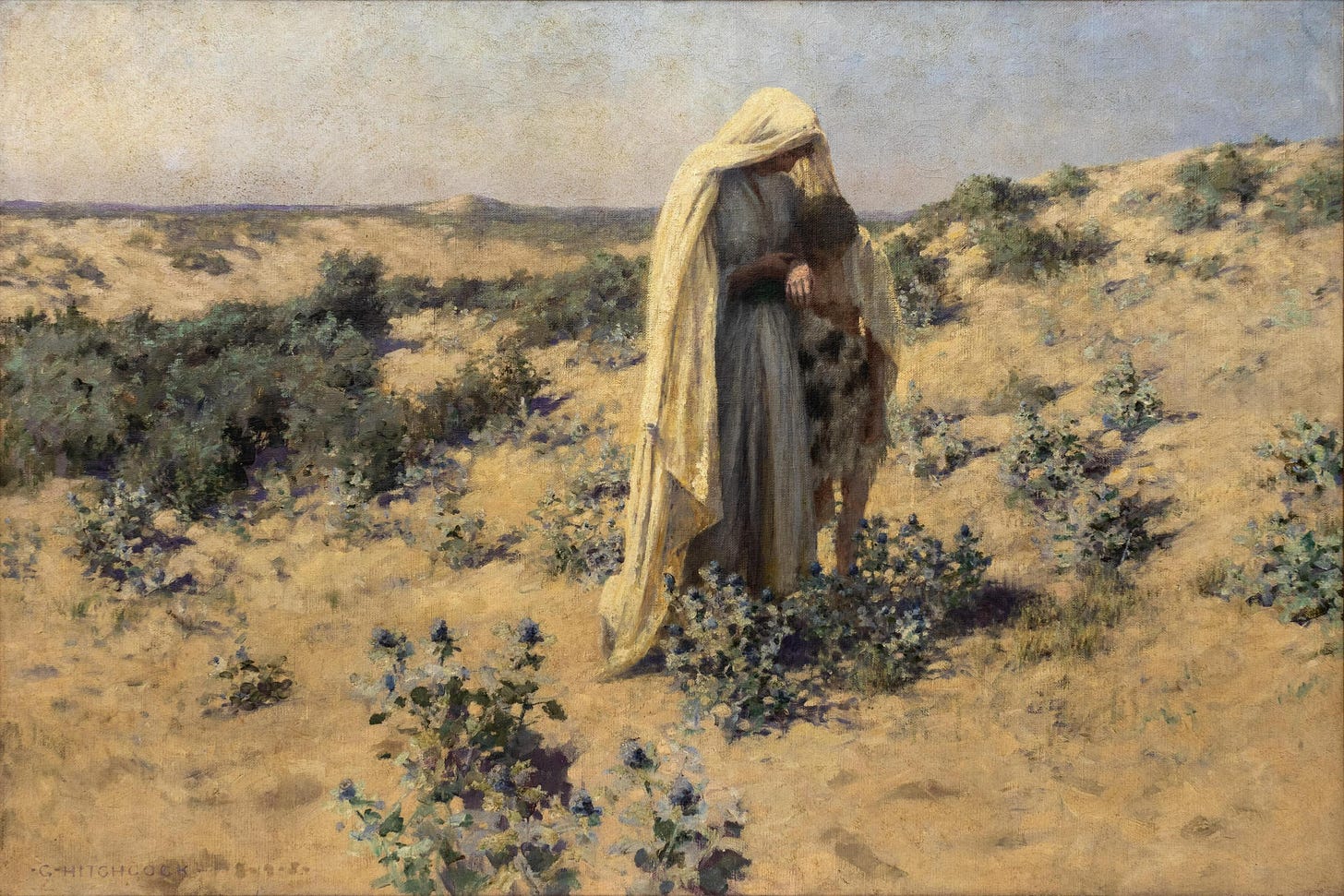

Such is the case with the story of Hagar, Sarah, and Abraham in Genesis 12–22. It is a story with aspects I find deeply moving and inspiring, while also feeling morally repulsed by the enslavement and abuse of Hagar, the use of Hagar’s body to give Abraham and Sarah a child, the endangerment of Ishmael, Hagar, and Sarah by Abraham, and the binding and near-sacrifice of Isaac. Though I am aware that some of these actions were permitted by the culture of the time, I believe these things are wrong—even morally abhorrent. I believe God does not ask parents to kill their children (even as a test or lesson), God does not ask us to sacrifice or endanger another person even in the pursuit of a worthy goal, and abuse is never even tacitly endorsed by God.

At the same time, I find that when I zoom out and look at Genesis 12–22 as a whole story—including the hard, immoral, repugnant parts—it has the capacity to tell a compelling and moving narrative about a God who is deeply invested in deliverance and human dignity.

Let me explain what I mean.

—Cecelia Proffit, “The God Who Sees”