Messy Conversations: When Loved Ones Leave the Faith

How to do your best when it matters most

The next words out of Kendra’s mouth will shape the future of her relationship with her daughter, Alyssa. At this moment, Kendra is staring slack-jawed at a computer screen having just heard Alyssa say shakily: “I’ve never believed in the Church. In fact, I hate it and the bigoted things it stands for.”

I’ve spent my career studying people who are capable of talking about emotionally risky things in a way that not only doesn’t damage their relationships but deepens them. Observing these people for thousands of hours has changed my life for the better.

My colleague, Jeff Strong and I, have recently found a strange group of people from which I’ve learned even more. I call them positive deviants. A positive deviant is someone who faces the same problems you and I do, but whose outcomes from those problems deviate positively from the rest of us. We found them by examining 514 stories of people who have had highly charged conversations about changing beliefs. Some were stories told by those leaving The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Some were told by friends, family and Church leaders with whom those people shared their startling news. The remarkable thing about highly devout positive deviants is that at the conclusion of their conversations the relationship was stronger than it was before. By contrast, the overwhelming majority of the rest of these conversations ended with alienation, contention and resentment.

For example, Kendra was delighted one morning to get a text from Alyssa, who lived with her husband, Chad and her first three grandchildren in another state.1 The text said simply, “Can you and Daddy do a Zoom at 7pm?” Kendra responded affirmatively. She warmed to the expectation of an announcement of grandchild number four.

Alyssa was her oldest child and had always been a dutiful and high-achieving girl in school and at Church. Alyssa read the Book of Mormon cover-to-cover before she got baptized at age 8. At age fourteen she began a habit of weekly temple service. Her husband, Chad, was cut from the same cloth—stalwart from birth to mission to temple marriage. They met at BYU and married in the temple seven months later.

At seven o’clock, Kendra and her husband waited happily for Alyssa and Chad to join the meeting. When their faces appeared at 7:03pm, they were solemn. Alyssa began with, “Mom, Dad, we can’t do it anymore. I’ve been living a lie for twenty-eight years.”

Kendra went limp. She felt an immediate sense of panic. Her mind raced to make sense of those incomprehensible words.

Alyssa’s eyes filled with tears. Her hand shook as reached for Chad’s, looked back into the camera and continued. Her next words were so searing that Kendra could remember them verbatim years later: “I’ve never believed in the Church.” Alyssa said shakily, “In fact, I hate it and the bigoted things it stands for. I’ve felt nothing but relief since I finally allowed myself to admit that. We have asked for our records to be removed. We still hope we can be part of the family but need you to know it’s not okay if Church is ever discussed around us.”

Kendra doesn’t remember conjuring the words that came unbidden out of her mouth. “This isn’t you talking, Alyssa. This is Chad, isn’t it? What kind of monster pulls a daughter and her children from her family?”

It was months before Kendra and Alyssa spoke again. And it was years before even a semblance of warmth returned.

The Bad News

The bad news from our study confirms what I’ve seen for 40 years: When it matters most we tend to do our worst. Our study found that the likelihood of a healthy conversation was lowest when someone with faith concerns speaks with either a close family member, an ecclesiastical leader, or someone very devout in their faith.

Devout. If they spoke with someone “very devout” the conversation was twice as likely to go badly as to go well. Sadly, the best prospect for a good conversation was to talk with someone whose Church commitment is marginal.

Family. Conversations with devout family members were similarly unsuccessful.

Church leaders. The lowest probability of a good outcome came from talking with an ecclesiastical leader: the conversation was 4.5 times more likely to go poorly as well.

To make matters worse, bad conversations tended to intensify people’s doubts. As a result, they were substantially more likely to accelerate their withdrawal from other devout members of their faith community.

But fortunately, there were positive deviants. Mandi, a returned missionary and her spouse met with a newly called bishop in their small Utah town to announce they were leaving the Church and wanted to be left alone. But something wonderful happened in that bishop’s office. Mandi described the conversation as “Awesome. Really, really good.” That bishop found a way to connect genuinely while compromising nothing. And he wasn’t alone. In subsequent years, the bishop and his wife developed a genuine friendship with Mandi and her husband.

While nothing can guarantee unicorns and rainbows, patterns emerged from the study that corresponded consistently with both parties enjoying authentic connection while acknowledging profound differences. I was happy to discover that you don’t have to soft pedal your beliefs to sustain warmth with those you love.

Here is how.

I. Take a Breather

Kendra just took an emotional gut punch. There’s no chance of a good outcome when you’re feeling confused, hurt, defensive or angry. You need psychological air. And the only way to get it is to lovingly bookmark the conversation with them, then start a conversation with you.

You just might need a breather if you’re gripped with:

Shame, Anger or Terror

Muteness

Defending of your faith

Fixation with fixing

Threats of damnation

Spontaneous aggressive testimony bearing

The difference between Kendra and the Bishop is that while the Bishop’s appointment just got tricky, Kendra’s world just got rocked. For her, hearing, “I’ve never believed in the Church. In fact, I hate it and the bigoted things it stands for” might feel like her entire life is now unmoored. Her unfortunate response was a TUI (Talking Under the Influence). It’s the verbal equivalent of a DUI (Driving Under the Influence). A DUI can land you in prison. A TUI locked Kendra away from her beloved daughter, son-in-law and grandchildren for years.

She lashed out because she felt threatened. Her heart rate was elevated, adrenaline was coursing through her circulatory system, her vision narrowed, her breathing was shallow and the large muscles of her arms and legs were engorged with blood. She was in no position to manage a highly sensitive interpersonal exchange. Her best move would have been to respectfully place a bookmark on the conversation. While we can’t control the outcome of a conversation, we can control its pace. It is always within our power to slow it down or even push pause. Reminding yourself of that power can restore a sense of efficacy that’s lost when someone drops a faith bomb.

Kendra may have avoided much misery if she had said something like:

“Alyssa, I can’t imagine what you are going through or how hard this conversation is for you. I’m sorry. I love you. And I hope you can understand that this is a lot for me, too. Please give me a little time to absorb this and get to a place where I can show up the way I want with you. Can we talk tomorrow?”

Notice there are two tasks—not just one—in placing a bookmark:

First, make a statement that validates them;

And second, make a statement that validates you.

Then politely take temporary leave.

II. Work on Me First

Most people have misplaced fears in these messy moments. They assume what they need is genius-level interpersonal skills. They don’t. The best predictor of the outcome of crucial conversations is thorough inside work, not masterful outside work.

Three tasks will put you in the best place to connect meaningfully with others:

Feel your feelings

Fix your story

Find your motive

Feel your feelings

If you feel tempted to skim this section and jump to the next, then you need this section more than anyone! Your dismissal of the need to pause and feel is evidence of either disconnection from your emotions, or your suspicion that emotions are for wimps. The truth is:

Ignorance of your emotions is not evidence of a lack of emotion. It’s evidence of disconnection. Unexpressed emotions don’t die. They go into the basement and lift weights. Then when they emerge, they do so in explosive ways through your behavior or your body. You might say things you later regret, or you may manifest mysterious physiological symptoms, or you may do both!

Emotions are for humans. Vulnerable expression of emotion is a mark of spiritual maturity. It puts you in company with “wimps” like Nephi who unabashedly expressed his despair (“O wretched man that I am!”2), Joseph Smith who put his momentary resentment of God in writing (“O God, where art thou? And where is the pavilion that covereth thy hiding place?”3), and even Jesus who was unashamed of His confusion and loneliness (“My God, My God, why has thou forsaken me?”4).

The path to peace is to take time to name and feel. You don’t have to wallow. You simply need to validate what you’re going through by identifying it and experiencing it. Suppressed emotions tend to intensify. Expressed emotions tend to subside. When you give yourself the grace to acknowledge what you’re feeling, the crashing waves begin to calm.

As you give them a name, you become capable of thinking about what you’re feeling. Naming emotions gives you the power to extract them from your body, hold them in front of you, and examine them. Which leads you to the second task.

Fix Your Story

Your second task will help transform your crisis into clarity. The emotions you’re feeling are not a consequence of what just happened to you. Your counselor in your bishopric telling you that he’s leaving the Church doesn’t make you feel anything. If it did, then every person who had that experience would feel the same thing. But they don’t. One bishop might feel sad. Another confused. Yet another could feel curious. And one may even feel empathetic. Why? Because different people tell different stories.

The emotions you feel are less a function of what happens and more a function of the story you tell yourself about what happens. For example, if the Bishop feels ashamed he may have told himself a story that his counselor’s departure means the Bishop failed him somehow. If the Bishop’s story is “What if I’ve been fooled, too?” he might feel scared. If his story is “You’re betraying me” he could feel angry. You’re feeling what you’re feeling right now because, whether you’re aware of it or not, somewhere inside you’ve decided it means something.

Your only hope of finding peace is to find your way to a peaceful story. Let me be clear: I am not suggesting you must be ambivalent about someone’s loss of faith! I’m simply suggesting that there is a way of holding what is happening that allows you to show up with love and faith. Our Father in Heaven can. The Savior can. With their help so can you. The path to that place involves identifying and fixing errors in your story.

But before you can fix it, you have to see it. The first step to seeing your story is to decode it from your emotions. If you’ve named and felt your emotions, you can now ask yourself,

“What story must I be telling myself to make me feel this way?”

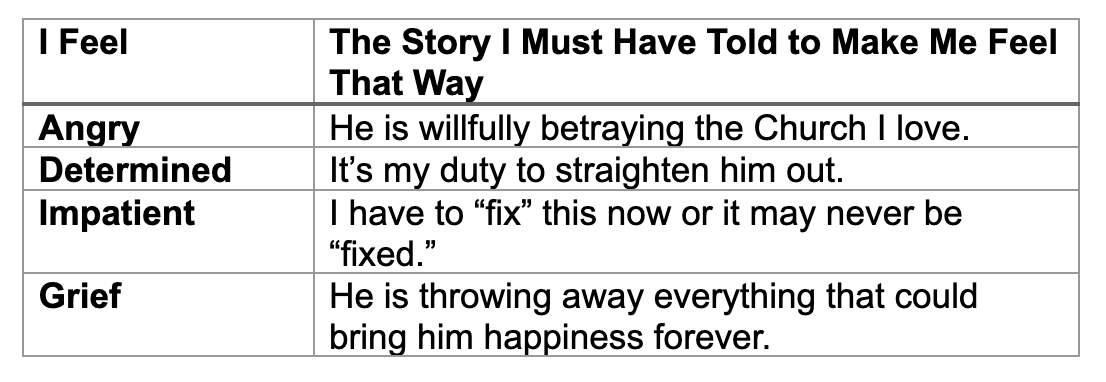

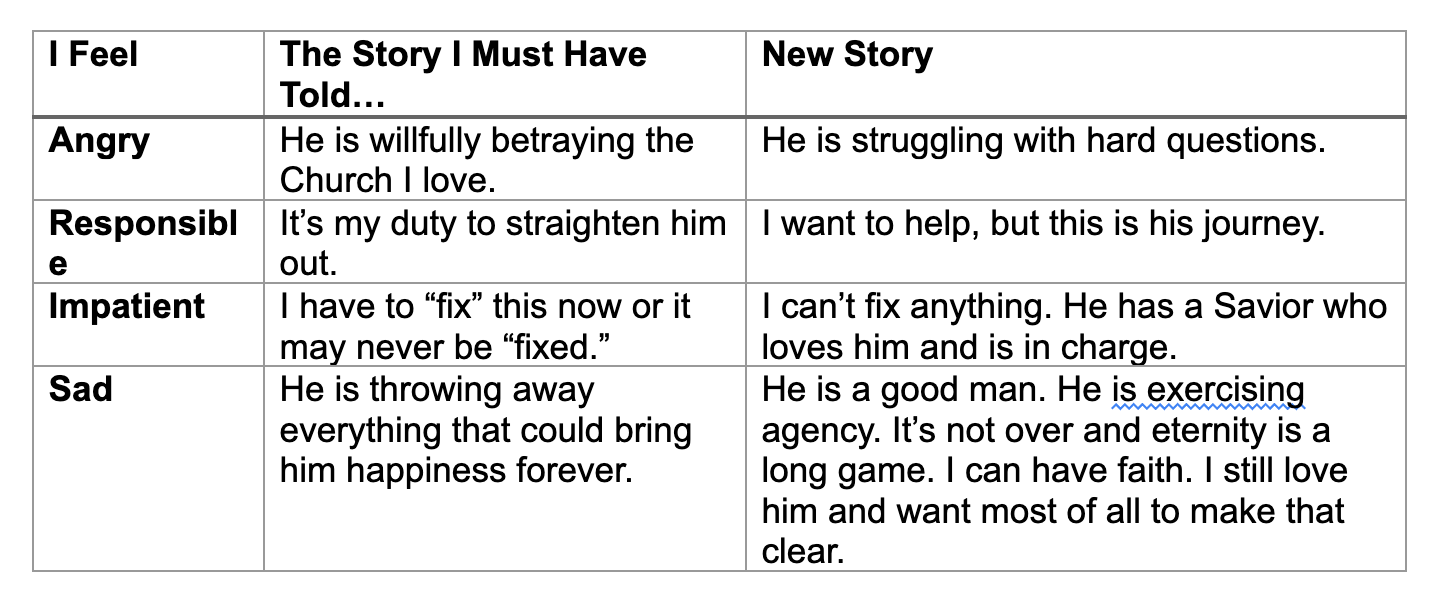

For example, Tad learned that Paul, one of his former young men, was leaving the Church in anger about its position on LGBTQ issues. After tracking him down, berating him, then urging him to confess the sins he suspected were the “real” reason for his “apostasy,” Tad returned home fuming and sad.

As a trained therapist, Tad had the presence that evening to reflect on what he had done. He took time to name and feel. He teased apart his turbulent stew of emotions. As he named them, he asked himself “What story must I have told myself to make me feel that way?” With some effort, he discerned the stories that had taken him to such an unproductive emotional place.

When Tad was satisfied that he understood what was going on inside him, the flaws in his story became apparent. He prayed for help to see the situation as the Savior would. In very little time, his story evolved.

As his story changed, so did his emotions. He felt settled, focused and tender toward his friend. Both prayer and wise friends can be a source of help as you work to reshape your story.

Find Your Motive

After working on what you think, your final task is to deliberate about what you want. If you don’t choose your motive, some lesser motive will choose you.

For example, Alejandro reported feeling “betrayed” and “lied to” after reading things about Church history he had never been told. “It took me three years,” he said, “to admit to myself and others that I didn’t believe anymore.”

He reports that when he left the Church he was ‘assaulted’ by a score of members who reached out in various ways to tell him how wrong he was. Many were people with whom he had never had a close relationship but now presumed to admonish him. He responded by separating completely from former brothers and sisters. For years he nursed a resentment of people he came to see as “false friends”—people whose affection for him was contingent on his agreement with their beliefs.

By far the worst response came from Rex, the father of a boy Alejandro grew up with. Rather than reach out directly, Rex sent him a lengthy epistle explaining how arrogant Alejandro was to think he knew more than scholars like Neal Maxwell, Russell Nelson, Hugh Nibley, Henry Eyring and a dozen others.

In the calm of reading this account, most of us would likely agree that sending a critical letter wasn’t a great strategy. But the problem wasn’t Rex’s strategy. It was his motive. Oddly, we’re often the last to know the motives that drive us. We think we’re just trying to “save a soul” when what’s really going on might be something less noble. Often the best way to identify what’s really driving us is to ask, “What am I acting like I want?”

What does Rex’s behavior suggest his motive was? When we feel socially or psychologically threatened, four motives that can possess us include:

Avoiding conflict

Being right

Coercing compliance

Punishing

It’s not hard to spot evidence of at least three of these in Rex’s behavior. His choice to write a letter rather than engage in the vulnerability of a face-to-face conversation might be about avoiding conflict. The length of the letter smacks of attempting to win a point rather than help Alejandro. And accusing Alejandro of arrogance crosses a line into bullying.

I don’t mean to accuse Rex of intentional evil. Far from it. As I said before, the challenge is that we are unconscious of motives that literally possess us in TUI moments. When strongly aroused, we’re not capable of complex self-reflection and thus, slide into unhelpful motives without realizing it. The good news, however, is that if you can see it, you can change it. The fastest way to get free of an unhealthy motive is just to admit you have it.

Let’s return to Kendra, the mother in the painful Zoom meeting. Had she taken a breather, named and felt her feelings, identified and fixed her story, then, after her outburst asked, “What am I acting like I want?” she may have recognized a desire to coerce and punish. And loving mother that she is, would have been repulsed by that awareness. Because she is basically a wonderful human being, simple awareness of a lower motives would be enough to invite change.

She could then “find her motive” by asking,

“What do I really want?”

I notice that when I reflect on this question absent the panic of the moment the Spirit helps me better align with God’s will. I find myself wanting to honor others’ agency, express love, speak my truth but also patiently understand theirs.

Some motives divide. They inflict hurt and division. Only one motive tends toward connection. In our study, the first clue to discovering it was asking subjects what kinds of behaviors intensified people’s doubts. Subjects almost unanimously agreed that they tended to dig in their heels when others responded to them with:

Lecturing and preaching – “Listen to me! Throughout history prophets have been unpopular, sweetheart. Opposition from the world is evidence we’re on the side of God.”

Judgment—”Leaving the Church is selfish! You’re not only putting our eternal family at risk you’re robbing my grandchildren of the opportunity to learn the Gospel.”

Arguing and debate—“All of your fuss about gender identity is just a social fad…”

We then asked if there were behaviors that helped them feel open to conversation. And finally we asked if there were behaviors that led to stronger relationships—even if their doubts persisted. The answers to both questions were precisely the same:

Active listening and validation.

Non-judgmental acceptance and love.

Acknowledging concerns and doubts.

So, what motive invites connection rather than division? What motive would naturally incline us to do all three of these helpful behaviors?

A sincere desire to understand.

Your final step in preparation for a meaningful conversation is to answer the question, “What do I really want?” Thoughtful pondering of this question under the influence of the Spirit will generally lead us to seek to understand rather than judge, coerce or punish. Pondering and writing your answers to this question will liberate you from the panic of the moment and orient you toward longer and richer goals.

What Next?

Having taken your breather, you’re now much less at risk of committing a TUI. But be aware that this inner work may need to be repeated. New provocations can occur that take you back to painful emotions, unhelpful stories and lower motives.

This repetition, however, is not redundant, it’s progressive. And even better, the very process of doing this work grows your soul. I believe that the friction of relationships is the process through which we become like God. Crucial conversations are the crucible of our discipleship. It is through this work of refining our stories and our motives that we become more holy and more capable of exalting relationships with those we love.

I have a suspicion that what will matter most in the hereafter will not be whether we arrived at some objective measure of perfection, but how well we’ve learned to love those who haven’t. In other words, people like us!

For example, Rex wrestled for three years over whether his real motive had been to stand for truth or something lesser. With eventual clarity, he sought out Alejandro and tearfully begged his forgiveness. He humbly explained that at the time he had been struggling with his own doubts. Furthermore, he was scared Alejandro would pull his son from the Church. This sacred moment neither compromised Rex’s faith nor restored Alejandro’s, but I believe it exalted both men.

The next step forward is to step boldly into uncertainty. Start by sharing your motive. Let them know you’re here to understand, not to fix or judge. Offer, but don’t demand the privilege of exploring their experience. And if permission is granted, seek to understand—and nothing more. Ask questions. Empathize. You needn’t agree with anything they say. Nor should you disagree. Simply remove your shoes and enter the holy ground of their life.

There will be future conversations as well. If this is a family member, you may need to have conversations about boundaries. You are not obligated to indulge every demand they make. Nor are they obligated to indulge yours. If you want to pray at meals together, you have a right to do so. If they don’t want to be in a room where praying happens, so be it. Find a way to respect your differences and share as much of life as you can.

I had just such a conversation with a son who left the Church. One of the most productive parts of our boundary conversation was our mutual acknowledgement of our own tendency to slide into evangelizing. During the conversation he told me he was comfortable with me making reference to happenings in Church as that’s a big part of my life. When he said that I felt a twinge of guilt, realizing I would likely use that opening manipulatively at times. I’d feel tempted to throw some spiritual chum into the conversation hoping to spontaneously reignite his testimony. I confessed this to him and committed to call it out when I felt it. And he agreed to inquire if he suspected it. He likewise confessed a weakness for adding Church-related snark into seemingly newsy chats. He invited my inspection when I felt it and pledged to hold himself accountable when he caught it first. That boundary has served us both well for years.

As I’ve suggested in previous articles and talks, the message of thousands of years of scripture history is that messy families and complex friendships are the norm, not a shameful exception. What God expects of us is to use the messiness as grist for our souls. It’s not only possible but the very purpose of creation to learn to forge ennobling and even exalting relationships in the most bewildering moments of our lives.

May we all be positive deviants in that great purpose.

I have taken liberty with stories from the study by combining elements from multiple subjects in order to create more succinct and representative samples of real experiences. I have also changed names and other identifying information to protect privacy.

2 Nephi 4:17

D&C 121:1

Matthew 27:46