What is the role of a prophet? What is the purpose of covenants?

Faith Matters resources to accompany your Come Follow Me study: September 22-28

The Lord supports me when He calls me to serve.

A life in Christ is an intimate partnership—so close that it feels like Christ is alive in our hearts. In this kind of life, our works come alive as a response to both life’s giftedness and its need. We anticipate the givenness of God from moment to moment. This life calls us to internal dimensions of sacredness and outward dimensions of love.

A life lived this way is a dance. One partner’s hand presses lightly upon his partner’s back, and she pivots to the left. His hip leads, hers follows. Her eyes glance right, he follows. Each subtle movement is complemented by reciprocity, animated by the shared rhythm. One partner pulls back, while the other reaches forward, both breathing in tandem. A concentrated attention on every movement is complemented by a countermovement, creating a fluidity in which her movements flow into his. When the partners in this divine dance are us and God, we learn to respond to what God offers and give something in return. This reciprocity creates a kind of uninterrupted unity.

The partnership of this dance feels to me like salvation.

—Hannah Packard Crowther, Gracing

The priesthood is “after the Order of the Son of God.”

“Offices are constantly evolving in a living church, they're constantly adjusting to revelation and to the needs of the people, and that’s okay. It really does open possibilities for women in the future.”

In the Greco-Roman world of early Christianity, women were considered inferior to men. Dr. Ariel Bybee Laughton says Christianity offered new ways to think about the roles of women in society, and their power and authority waxed and waned over time. We discuss her chapter “Church Organization: Priesthood Office and Women’s Leadership Roles” from the book Ancient Christians: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints.

What is the role of women in the Church? We’ve had several conversations around this important, tender topic, and are committed to continuing to host thoughtful conversations about this. Find our previous conversations on this topic in our “Women and the Priesthood” tag:

The Lord’s servants are “upheld by the confidence, faith, and prayer of the Church.”

Tyler Johnson reflects on Melissa Inouye’s powerful perspective on what it means to sustain past Church leaders and their teachings, even when problematic:

Specifically, she compared Brigham Young’s racial animus to her own vomit. She observed that once when she was sick from chemotherapy, she vomited all over her kitchen table—and so her loving husband came, and tenderly cleaned up the sick. To not do so, she observed, would have been as illogical as it would have been callous. The mess was simply a fact amidst her life in this broken-down world. It was part of the reality of being in a place where something as terrible as cancer can ravage even the healthiest of bodies, where even the treatments that are supposed to make the cancer “better” can leave the person with symptoms that often seem worse than the disease.

Similarly, she said, she had confidence that Brigham Young (and others like him) now recognize that their racism was wrong—and that they look to us, their spiritual descendants, to be confident that they now know it was wrong. She was confident, she said, that those church leaders from days past need us to clean up the messes that racism has left behind, just as her husband cleaned up the mess when she was sick.

…At first, the comparison seems a bit uncomfortable. For those of us who came of age dutifully singing “Follow the Prophet! Follow the Prophet! Follow the Prophet, he knows the wa-ay!” The prospect that something a past prophet said would need “cleaning up” may initially strike us unnerving. But once we push past that initial discomfort, we find that this comparison flows from love and an attempt to develop a holy historical empathy.

—Tyler Johnson, “Embracing the Pain of Paradox”

Prophets and Apostles testify of Jesus Christ. The Lord’s chosen servants lead His Church.

What is a prophet, and what is a priest? Why does it matter that the President of the LDS Church is both a prophet and a priest? How can better understanding each of those roles change how we experience our membership in the Church? Learn from Matthew Bowman in “The Prophet and the Priest,” an essay on WayfareMagazine.org:

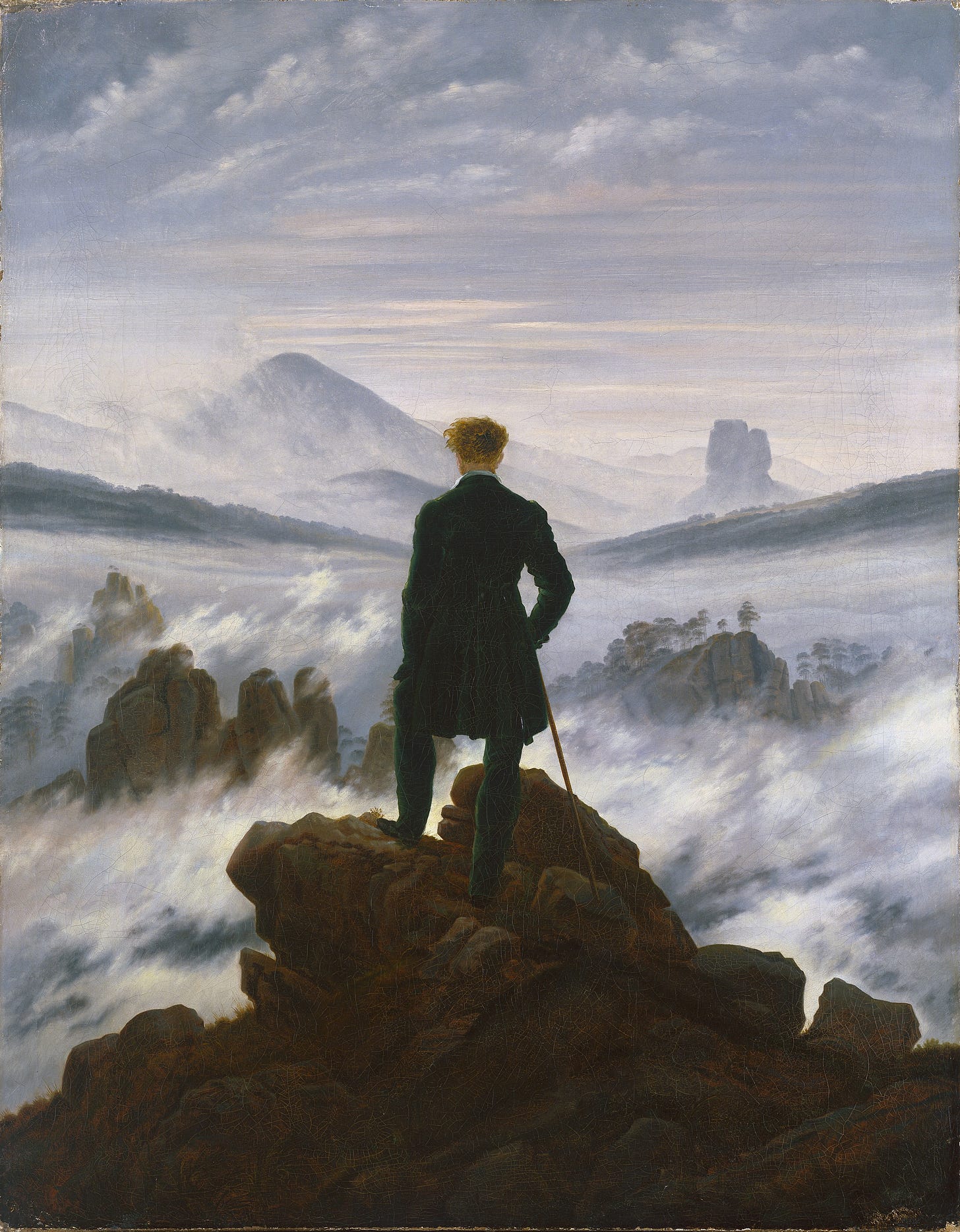

This painting is considered one of the masterpieces of the German Romantic era, the quintessential Rückenfigur painting. This style of painting depicts its primary subject from the back, robbing us of the opportunity to see the figure’s face and thus focusing us on what the figure is experiencing. In the case of this painting, it brings our sight toward the landscape upon which the central figure gazes, sometimes seen as representing “the sublime.”

I love this painting as a metaphor for the prophetic project for multiple reasons. The first is that the painting pulls us away from the prophet himself and toward that to which the prophets point us—the sublime in the painting, Jesus Christ in our theology. Beyond that, the painting reminds me that prophets, too, are humans just like we are. The figure in the painting, though depicted in the foreground, remains dwarfed by the landscape he is beholding—he is not a titan, not a colossus, but a man faced with an overwhelming scene.

—Tyler Johnson, “What the Prophet Saw”

The Lord accomplishes His work through councils.

I can be careful in living my covenants.

The covenants we all know best, of course, are those that we take on at baptism, and when we partake of the sacrament each week.

When, as part of those covenants, we take Christ’s name upon us, we are joining a family, and accepting obligations not only to the sovereign, but to all of his other subjects as well. These covenants to each other are clearly laid out by Alma at the Waters of Mormon in the familiar passage in Mosiah, in which Alma bids his followers to come into the fold of God, and to be called his people, to bear one another’s burdens and mourn together and give comfort to one another.

We often try to read these verses as a contract, as though we could check off “mourn with those that mourn” on Monday, “comfort those that stand in need of comfort” on Tuesday, and put “stand as witness of God” at the top of our lists every day, and somehow fulfill our obligations. But of course we can’t—those obligations are open-ended and infinite; the nature of the world is such that there will always be mourning and comforting to do, and our witness of God’s love will always be incomplete.

—Kristine Haglund, “Covenants & Contracts”

Church members often talk about “covenants” as though they are contracts in which each signatory promises something contingent upon the performance of the other, as though the relationship with God established in the temple endowment ceremony is comparable to executing a mortgage agreement.

But I think that sort of interpretation reflects, again, the world of shopping and commerce modern Americans are used to, when in fact the implication of the rituals themselves points less to commercial contracts, in which two people exchange something, than to the establishment of kinships, which are personal relationships that cannot be obliterated even when one party behaves badly. All throughout scripture, after all, God declares that his covenant with his people will never be canceled even if the people violate it. Isaiah 54:10, for instance:

For the mountains shall depart, and the hills be removed; but my kindness shall not depart from thee, neither shall the covenant of my peace be removed, saith the Lord that hath mercy on thee.

The rituals of Latter-day Saint worship, I think, point us in this direction. They don’t exist to give us information that we need to better fulfill a contract. Instead, they invite us to behave as though we are always already in relationships in which we give to each other out of care and kinship.

—Matthew Bowman, “Rituals of Becoming”