How should we read the Old Testament?

Faith Matters resources to accompany your Come Follow Me study: December 29-Jan 4

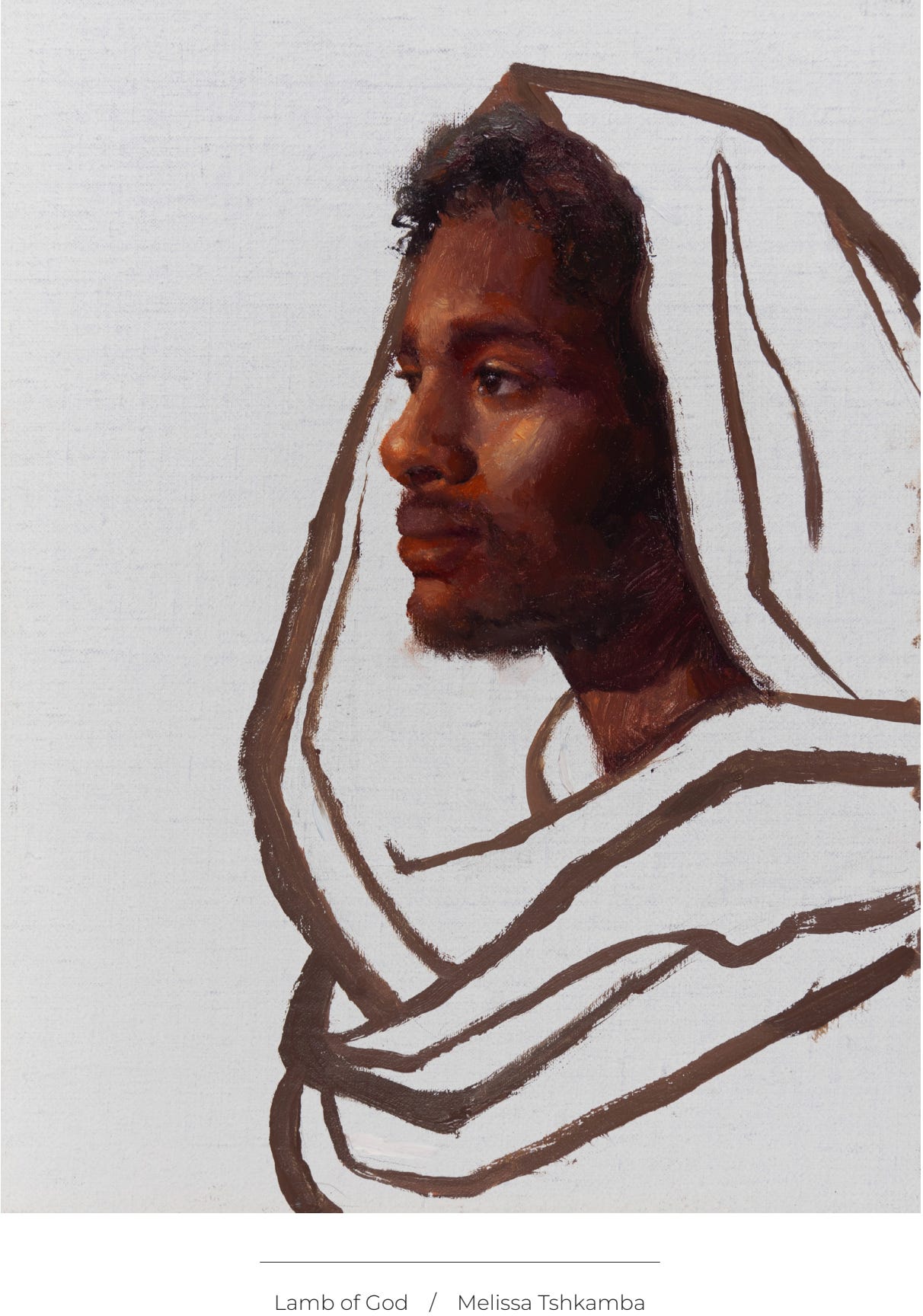

The Old Testament testifies of Jesus Christ. I can learn of Jesus Christ in the Old Testament.

I feel like I grew up reading scripture, being trained to look for what you’re supposed to do. Like they were sort of instruction manuals and examples of people I should live my life like. Like go be courageous like Esther, you’re supposed to have the faith of whoever, like oh go learn how to live your life from the scriptures.

And then I encountered the story of Jacob from Genesis… and when I read it I was like… nobody wants to be like him! And then the rest of the children of Israel, I was like, that’s a dumpster fire! I don’t want to read that story to my kids at night as like the hero series book!

But then I was like, wait, that actually makes me love their stories even more. Because when you read them, you’re like, there’s no hero in this story. And then it’s like, oh, exactly. The hero spot has been left open for who the true hero really is of scripture. And I started to read scripture differently. I want to look for, what do I learn about the heart and the nature and the character of God when I read. That’s my number one approach to reading scripture.

Then it became worshipful, because I read them not for instruction sake, although I think they give great advice. But my thought process is, I’m reading them for good news, not good advice.

—Dave Butler, “Infinite Ways to God”

The point of Scripture is not to tell us something. The point of Scripture is to do something. The point of Scripture is to introduce us to God and invite us to participate with God in the revelation of who and what He is. …

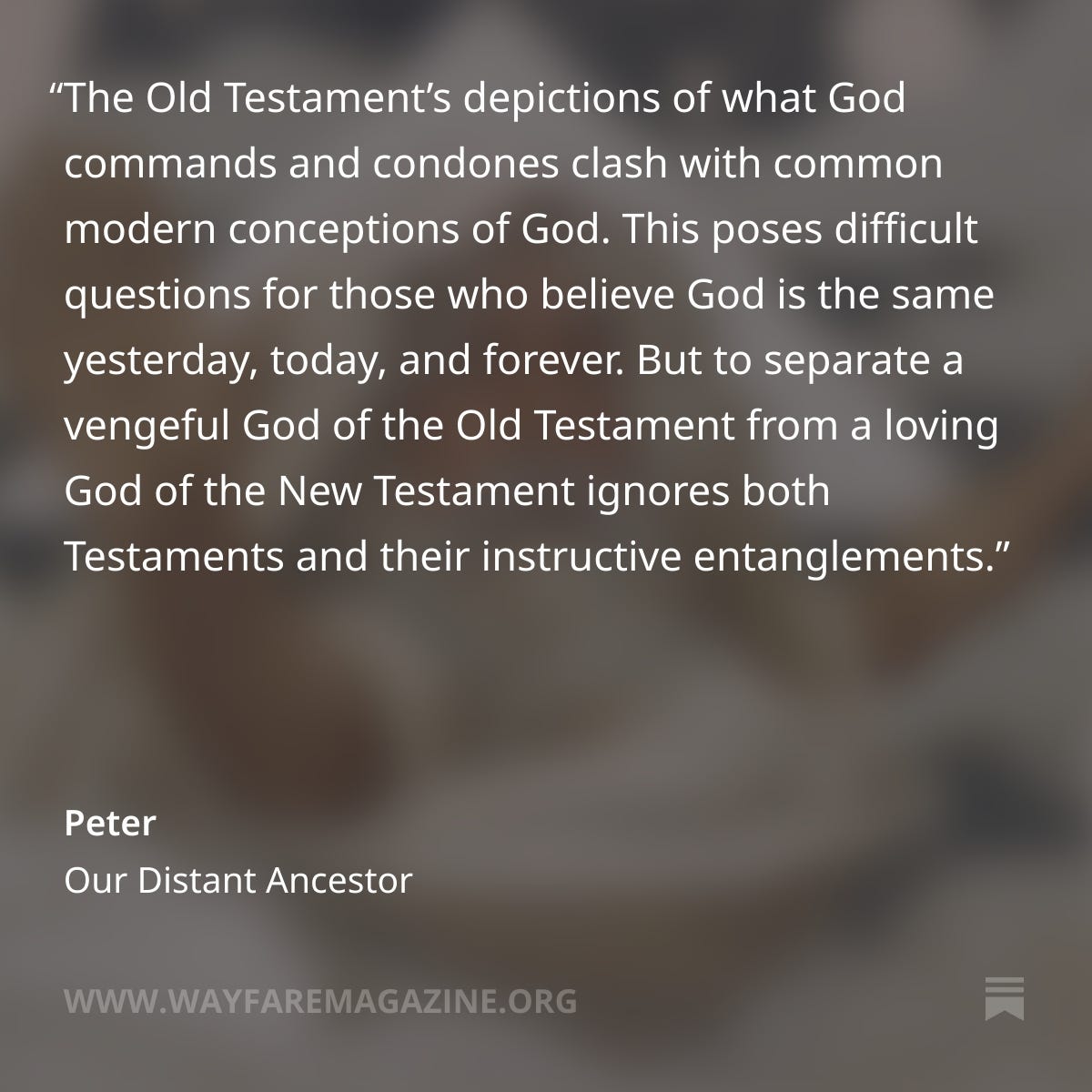

We probably in general do Scripture a disservice if we come into our reading of it with the expectation that it’s going to provide something like a consistent, systematic account of the nature of God and the whole of reality and our place in it. In my experience, it’s not that kind of thing.

Scripture is a kind of grab bag of thousands of years worth of often profoundly divergent descriptions of different experiences that people have had of God, both individually and collectively.

And, as scripture, it’s my responsibility to take all of those accounts seriously, but it’s my responsibility especially to take them seriously as occasions for God to reveal himself to me, not as occasions for me to simply nod my head and agree with whatever I think it says at the surface level of the text.

—Adam Miller, “Seven Gospels”

I read the Bible in the morning. It’s my founding text, the narrative I locate myself in. Its strange oblique stories act as a counterweight to the cultural soup I’m swimming in the rest of the time. It never fails to provoke, inspire or infuriate me.

I am currently reading the Bible with a group of friends. We call it “wild Bible study” because in reading and chatting together we are not after one right answer, not seeking to solve anything. I used to try to read it like this, not least because many Bible study notes do make it feel like the text is a puzzle to be solved, its vivid and dense language in need of putting into doctrinal boxes. I found that approach boring, so I stopped going to Bible studies. Now I don’t worry that there are many things I don’t understand, whole books and passages I don’t know what to do with. I don’t think either Bible reading or faith itself is about resolution. It is a lot more like poetry, drama or music, which any good teacher will tell you are not completely amenable to the question “But what does it mean?”

I want only to keep tasting it, turning it up to the light like a crystal to see just how much it holds.

—Elizabeth Oldfield, “Attending to Life”

I don’t think the Bible gives us certainty. I think it gives us a sort of a quilt of beliefs, or a diverse set of of religious expressions that span over a thousand years. And we get to enter into that. But to suggest that we’re going to derive from that certainty, is I think setting us up for a big fall.

—Pete Enns, “The Sin of Certainty”

The Bible isn’t a law book. The Bible is a library. And the value of a library is not that it tells you what to think, but that it teaches you how to think by showing you the history of people changing their thinking.

—Brian McLaren, “Embracing and Challenging Scripture”

Jesus Christ is Jehovah in the Old Testament.

Paul says the greatest picture and manifestation of the heart of God that we have is Jesus on the cross. There are pictures of his love and there are pictures of his character throughout scripture. But the one that’s nearest, Paul says, to who he is, is Jesus on the cross.

… I read 1 Samuel and I say, that does not look like the self-sacrificing God on the cross, so there’s something wrong with that picture. My understanding of it, the transmission of it, even I’d go so far as to say Samuel’s interpretation of the revelation could have been wrong. … I don’t know what it is. But what I do know is there is something I am not understanding or something wrong about that particular story. Because the construction of the Bible, there’s so much in there. Who wrote it? When was it written down? What was your source? What did they assume?

… I’m really hesitant to throw away the nature of God by a story like that. And so one I do have that is nearest and closest to the character of God is Jesus on the cross. And so I begin there always. That’s what he’s like. That’s how devoted he is to me. That’s how far he was willing to go to rescue me.

So I do see stories that contradict Jesus on the cross. And I just say, Oh, I actually am going to take Jesus on the cross as my measuring stick. I’m going to measure every story against that one.

—Dave Butler, “Infinite Ways to God”

The Lord restored many “plain and precious things” through Joseph Smith.

Joseph Smith made it abundantly clear that he was not part of the evangelical tradition that was working toward a model of inerrancy. Quite the contrary…

He gives us the Book of Moses as a kind of an addendum, but also kind of corrective to many of the incorrect definitions, descriptions of God and his interactions that take place in the Bible.

It’s also the case that in very recent years, both Elder Oaks and Elder Holland have used almost identical language to say, we do not believe the scriptures are the source of ultimate truth. They both use that exact language, right? They say, the spirit is the source.

The scriptures are an imperfect reflection that is filtered through culture and history and individual fallible minds. And so I think the important thing is to approach the Old Testament with respect and with deference and with a kind of intellectual humility that we don’t have all the answers and we can’t make all the pieces fit together perfectly.

…I and Fiona think that Moses 7 was given by direct revelation in our day in the context of trying to correct the damage done to the plain and precious truths, and so it has a higher place in our canon of inspired writ.

And so for us, the God who weeps with us and sorrows with us is the standard by which we evaluate what we think are some less than inspired depictions in scriptures.

—Terryl Givens, “So Who Wrote the Bible?”

The Old Testament helps me understand my covenant relationship with God.

The greatest heresy in the history of monotheism is a misunderstanding of chosen-ness. It is the assumption that some are chosen for exclusive privilege, when in fact to be chosen by God is to be chosen for loving service. …

There’s this set of dynamic tensions that God says to Abraham. God says, I’ve chosen you to bless you and to be a blessing. I will make you a great nation, but through you, all the nations of the world will be blessed. …

The blessing is not exclusive. It’s instrumental. And that sense of being chosen, that chosen-ness, doesn’t mean that I’m better than anybody else. It means I’ve been chosen because God loves everybody. I have the privilege of trying to be a channel of of God’s love, not to people I’m superior to or separated from, but to people who God loves too.

—Brian McLaren, “Life After Doom”

I heard a Jewish rabbi speak, and something became clear. While this rabbi was only tangentially speaking about covenants, he reframed them for me. He said that he was sometimes asked by people who were not Jewish, “What makes you so special?” The implication was, “What gives you the arrogance to call yourselves a chosen people?” Latter-day Saints could ask themselves this same question: among the billions of people who have lived on earth, why would God give this unique piece of saving information to just a few favorites? Who made us the teacher’s pet?

The rabbi’s response to this question was simple: God chooses those who choose Him.

This felt like a mic drop moment. It was so basic. Could it be that this was the essence of covenant? Fundamentally, it’s not about reciprocal duties, but rather, reciprocal relationship?

And could it be that at the heart of every covenant we make is this one same truth? It’s not just separate and distinct agreements made at baptism, during the sacrament, and in the temple. It’s not a legal contract with pages of clauses. It’s one promise. It’s one choice. It’s saying yes to gracing. Fundamentally, it’s not making covenants (plural), it’s living in covenant (singular). It’s living in Christ.

—Hannah Packard Crowther, “Dancing with Christ”

The central component of that covenant is relationship with God. Relationship with others also, but especially relationship with God.

Through covenants, our Heavenly Parents collaborate with us in the messy fields of life. Living covenants requires not only faith but also action and longing, even in the face of darkened belief. Covenants are an urgent invitation to hold onto God the same way he holds onto us, allowing God to continually return to us. Like the energy required to create a chemical bond between two atoms, covenants motivate us to form bonds with the people around us even when it is difficult. Covenants immerse all in Christ’s love. They are the shape of God’s embrace.

—Tyler Johnson, “Why Covenant?”

Read what other Wayfare authors have written about covenants and covenant living here.

Heavenly Father wants to make covenants with me.

I’m sure you have heard that you will make covenants. And you have probably been told that covenants are like promises. You promise to do some things, and God promises to do others. And that’s true.

So far, you have made fairly simple promises. You promised you would go to bed after one more story. You promised you would eat what I made without complaining next time. And while those are pretty small promises, you were not able to keep them. But the covenants you will make at baptism are so much bigger and so much harder. You will promise to always remember God, always stand as a witness at all times, in all things, in all places. Every thought, word, action, all turned over to God. How do you even begin to try to do that?

I don’t know. After twenty-five years of trying myself, I have not managed to keep the promises you are about to make. Not even close. I was baptized when I was eight, and I have been underwater ever since, drowning in commitments that I am still completely inadequate to uphold.

If you are like me, and there’s good DNA evidence to suggest that you are, then you are not going to be able to keep your covenants. You will fail. And you will fail often. You will fall flat on your pants, and then you will shake yourself off and say, “Okay, I’ll get it right this time.” But you won’t.

Instead, you will make even bigger, more impossible promises. Promises like, “I’ll give everything I have and am to God.” But you won’t do that either, even though you try really hard. And you will probably become frustrated and embarrassed. And at some point you might wonder, what is the point of making so many promises that you are never going to be able to keep?

… I think the point is that you can work and strain all your life to pay your debts, to keep your covenants. Maybe you could even manage to do it all perfectly. Read your scriptures daily, pray always, get to church ten minutes early, etc. And still you could entirely miss the point. The point of your covenants is not to fulfill a contract, or balance a checkbook, or climb your way out of a debt. The point is the relationship. The point is being God’s son.

—Sarah Perkins Sabey, “Covenants by Immersion”