How and why does the Church change? Is it okay to work for change in the Church?

Faith Matters resources to accompany your Come Follow Me study: December 8-14

I believe in the gospel of Jesus Christ.

God is not a concept, an idea, something frozen in time. God is a person, and thus encountering God is not about mastering a rigorous set of doctrines, but understanding and trusting in the bonds of a relationship that will inevitably change over time, just as your relationship with those you trust most will change over time.

The heartbeat of that relationship is what religion is: something living, something that grows and evolves, something that flourishes in different ways in different times and places.

The fact that religion is living can give hope. Jesus is calling in every language, in every time. Having faith is having the hope to live in the world that being religious promises is possible and acting on that hope; to be willing to turn your back on the temptation of sterile idolatry and to plunge into the possibility and blessed reality of change.

—Matt Bowman, “Spiritual Cartography”

The Church of Jesus Christ is guided by revelation.

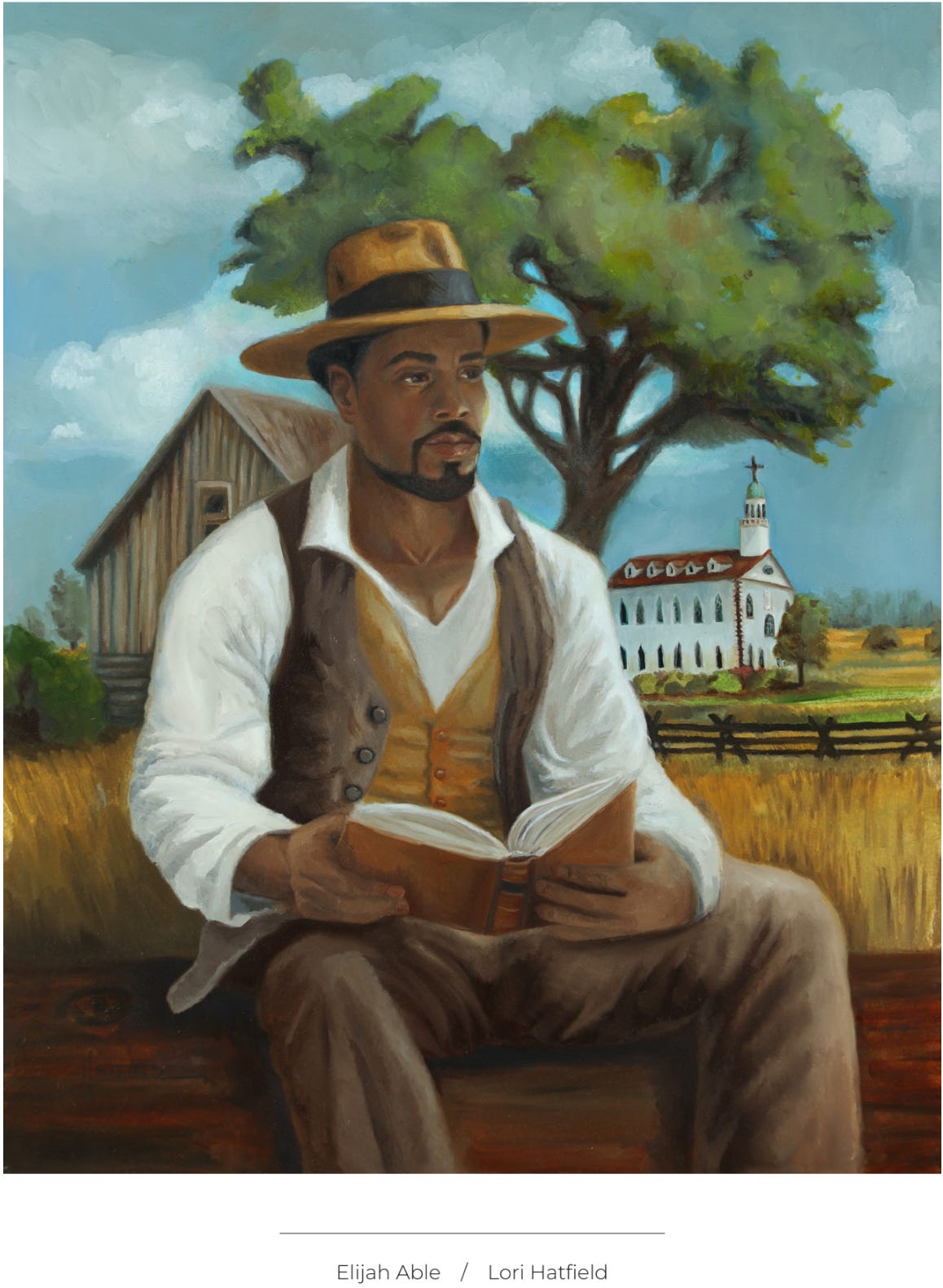

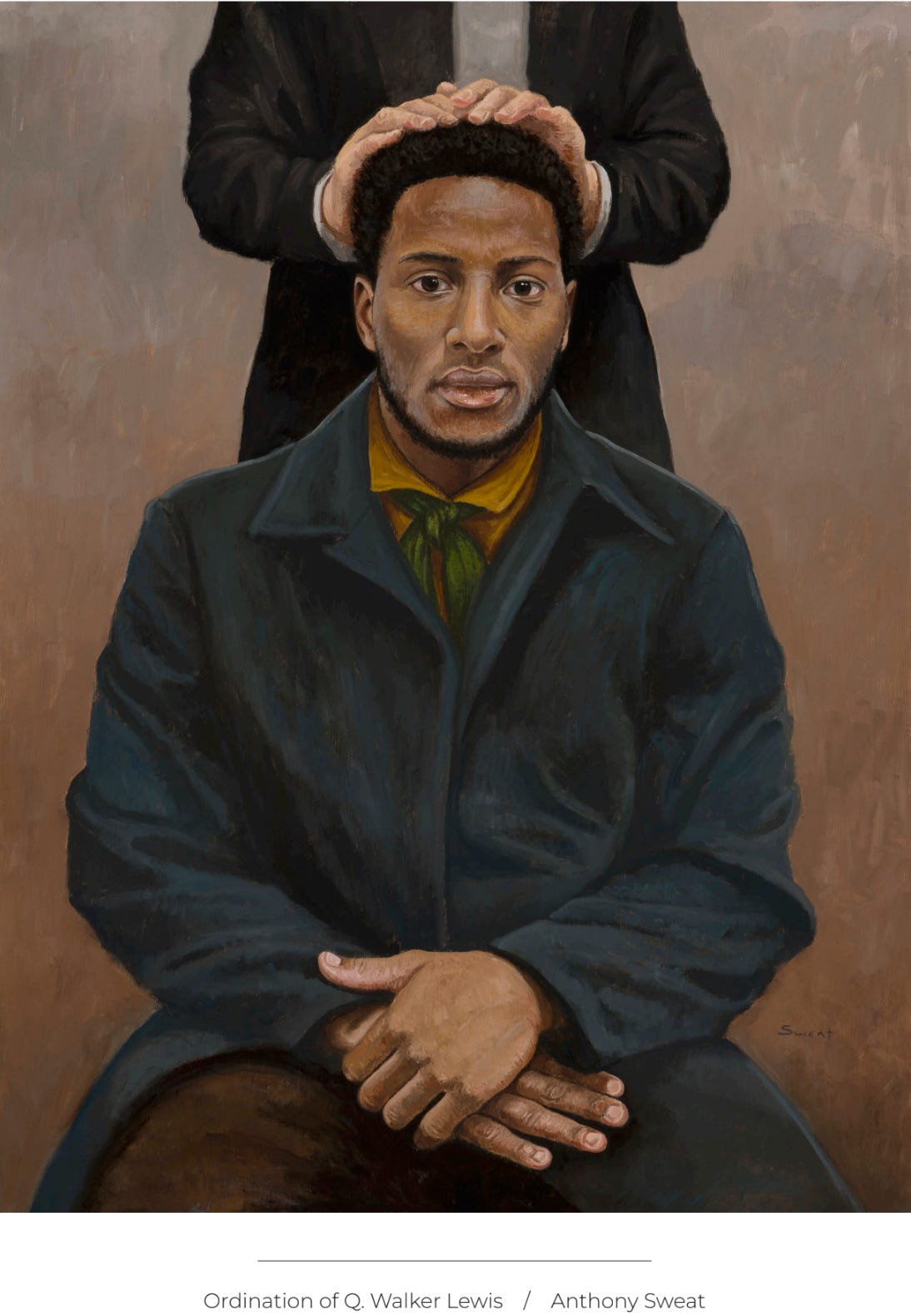

We sometimes talk about the 1978 revelation as if it came out of nowhere—a sudden command from heaven. But Matt helps us see the reality that this was a process shaped by years of thoughtful wrestling and dialogue, courageous individuals who quietly worked to open hearts and minds, and the unwavering faith of Black members who carried impossible burdens with grace and conviction.

In our conversation with Matt Harris, we explored what it means to be part of a living church—one that’s capable of change, because it’s built on continuing revelation. We talked about how “doctrine” has been defined and redefined across the Church’s history, and about the vital role each of us plays in the process of institutional revelation. This isn’t just about the past, it’s about how we show up today—how we answer President Nelson’s call to root out racism and build a more inclusive future within the body of Christ.

We’re deeply grateful to Matt for his careful, bold work.

Faithful Church members believe that Church leaders determine policy and doctrine based on the principle of revelation: communication from God to humans authorized to act for him.

But how does that revelation happen? On that answer hinges the larger question of whether agitation and provocation are, or can be, helpful or appropriate.

Though there’s certainly much more nuance to it than this, it may be fair to consider two competing revelatory schools of thought; let’s call them the text message theory and the buffet theory.

In the text message theory, God sends communication similar to how we send text messages. The message is clear and free of much need for interpretation. The receiver has no control over where or when they’re received, much less what they say. The text message theory is communication from God, in God’s own way and on God’s own timing; free of context, free of outside pressures, free of the opinions or bias of the person receiving it. It’s God’s will, unfiltered.

Subscription to the text message theory requires, more than anything else, a belief that there is a crystal clear channel of communication between God and person — that the sender sends unambiguous messages and the receiver is able to understand them.

The buffet theory stands in contrast to the text message theory. Imagine how you eat at a buffet — you make your way between tables, considering at a variety of options, until something grabs your attention and get a little nudge toward a particular item. You take some of that, because it was there, in front you, and it felt right at the time.

In the buffet theory, revelation works similarly. Our communication with God doesn’t happen in an unfiltered, clear, and contextless channel. Rather, we have in front of us a variety of options; these options could be situational, placed in front of us due to circumstances beyond our control; they could be logical, having arrived at them by study and analysis; they could be interpersonal, as we’re urged and persuaded by others to take a particular course. They could be right, or they could be wrong. We look at the available options, ask for guidance, and, hopefully, get a nudge in the right direction.

While I don’t believe that either method is the only way to receive revelation (and perhaps, someday, I’ll share my one personal experience that felt like a text message), I’d guess that most faithful Latter-day Saints relate more to the buffet theory than the text message theory. My own consistent experiences and many of those shared privately with me tend to fall within those parameters. The stories I hear related during fast and testimony meetings are often similar and seem to follow that pattern as well.

The question remains, though, if those we consider prophets receive revelation that way too: by examining the options around them — some of which are right, and some of which are wrong — and doing their best to follow a divine nudge which, at times, can be hard to discern.

I think there’s often a sense that while we rank-and-file members may be dining at the revelatory buffet, our leaders more often receive divine text messages — messages that are free of ambiguity or need for interpretation, and that take place completely independent of the receiver’s cultural context or chronological whereabouts.

I think though, that with some examination of history and Church leaders’ own words, we may come to a different conclusion.

—Tim Chaves

Is it ok to try to fix the Church?

We can carry the church beyond its “cruder stages of development.” Though it won’t happen all at once, we can be — in the words of one of my favorite LDS thinkers — “faithful provocateurs” who directly or indirectly recast the Church more fully in the image of the God we believe in; one who is no respecter of persons, prejudices, or past; one whose love is unlimited and extends to enfold each of his children.

The work of God must move forward.

Theology is not God working in the world. Theology is how human beings make sense of God working in the world. … The way we talk about how God works in the world changes. It might change because God is working in the world. It might change because we have differing things that we emphasize. It might change because we learn some other thing that now informs the way we think about God’s working in the world. But the fact that theology changes, just means that our understanding of God’s working in the world has changed.

But the important thing about the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is not it has the perfect theology that gives us the answer to everything in the world. The important thing about the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is doing God’s work in the world, and it has a necessary and vital role that God has given to it in his work in the world, and it’s trying to do that work.

—Nate Oman

I can trust in the Lord, even when I do not have a perfect understanding.

Is it okay to work for change in the church?

Is there a faithful way to push for change in an institution one believes is divinely guided? What does it means to belong to a Church that values both institutional authority and ongoing revelation?

In this candid discussion, Lisa and Scott reflect on the Church’s evolving approach to its own history through the years. They both share a deep commitment to transparency and accuracy and discuss how Saints takes deliberate steps to address challenging topics—including the priesthood and temple ban, the Church’s rapid global growth and subsequent correlation efforts of the 1960s, and how those changes shaped women’s roles and autonomy within the community.

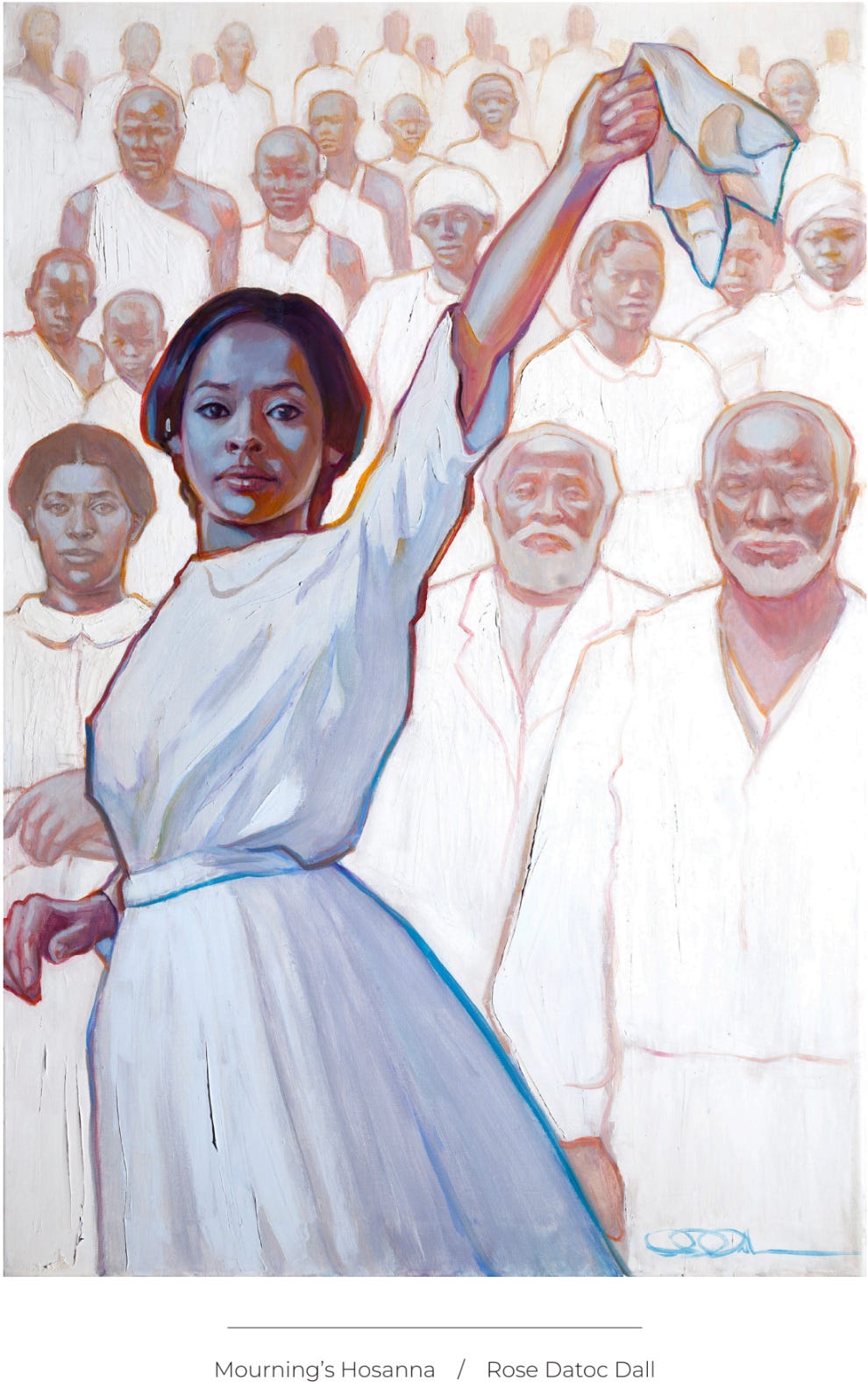

They share powerful stories of ordinary members navigating these pivotal moments. From Black Latter-day Saints who held onto hope during the painful years before 1978 to those who quietly and actively worked for change, these stories offer a vision of discipleship that embraced courage, resilience, creativity, and deep faith—a model that feels especially relevant today.

This conversation was a beautiful reminder that each of us is part of a rich, unfolding history—a history that connects us to generations of Saints who faced their own challenges and whose courage and faithfulness have blessed us today. We hope it inspires you to see your own place in this story.

How can I make sense of our history of denying priesthood and temple blessings to our Black brothers and sisters?

There is no tidy or pretty answer to this question. But it is a question that, if openly engaged, can teach us a great deal. Read Paul Reeve's essay "Making Sense of the Church's History on Race," and listen to his conversation with Terryl Givens on "The Real Story of the Priesthood-Temple Ban" here.

Learn even more from the perspectives of Black Latter-day Saints by exploring our “Race and Racism” tag.

The Lord guides His Church through His prophet. Prophets help us know the will of Heavenly Father.

In this conversation, Matt draws on ancient scripture to explore two archetypes that show up again and again: the prophet and the priest.

The prophet, Matt says, is often a voice from the outside—someone who has had a powerful, personal encounter with the divine and is sent to deliver a message that calls the community to repent. They challenge, critique, and call us back to our spiritual roots.

The priest, by contrast, usually nurtures from within—building and sustaining community, preserving memory, and ministering through sacred ritual. The priest creates belonging, continuity, and connection.

And while these approaches may seem to contrast, they work in harmony to support and strengthen the spiritual life of a community.

Matt notes that beginning around the 1950s, we began consistently referring to the president of the church as the prophet. And he wonders if, in doing so, we may have come to sometimes undervalue the essential priestly work the President of the Church also does.

This conversation helped us see something familiar—and deeply cherished in our tradition—in a fresh and powerful way and we came away feeling more grateful for a structure that makes room for both priestly care and prophetic vision.

You can also read Matt’s essay for Wayfare that inspired this conversation here: